Ankle Mobility for Rowers

This is the final installment of mobility for rowers, where we’ll cover the importance of ankle mobility for rowers and how you can improve flexibility and strength in the calf and shin muscles for better compression, cleaner catches, and stronger drives. In Part 1, we discussed what “tightness” really is (and what it isn’t), why mobility is so much more than just flexibility alone, and how to address mobility restrictions in the thoracic spine. In Part 2, we broke down the big bad hip flexor muscles. In Part 3, we went to the posterior hip and dug deep into the glute muscles. The goal of mobility training is to improve flexibility, strength, and stability in major muscle areas to improve rowing performance and reduce risk of common rowing injuries. Knee, hip, and low back pain often happens as a result of something going on at the start of the kinetic chain. Ankle mobility for rowers is crucial to set the rest of the body up for great performance and to minimize excess force on other structures.

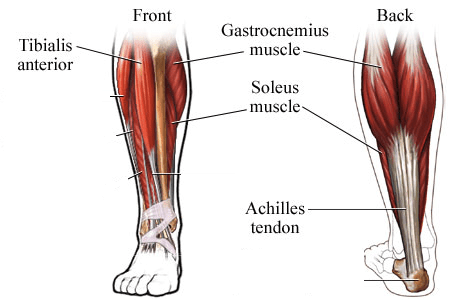

Restriction: Calf muscles (gastrocnemius, soleus), shin (tibialis anterior), bottom of the foot

Location: Calf area, shin area, feet

Test: Power Rack Test

Rowing fault: Poor compression, splayed legs at the catch, poor leg drive at the catch from being in an unstable position

Ankle Function in Rowing

Poor ankle mobility results from muscles of the lower leg, including the calf muscles of the soleus and gastrocnemius, and the tibialis anterior and posterior, and even the plantar fascia at the bottom of the foot. The plantar fascia is a sheet of connective tissue covering the muscles on the bottom of the foot. Any of these tissues can become restricted, resulting in poor mobility of the ankle. Ankle mobility for rowers is important to maximize effective length and power in the stroke. A restriction here will limit the rowers’ ability to get to full compression without another fault at the catch. For example, rowers with poor ankle mobility may splay their legs at the catch, lift excessively from the heels, or round at the lumbar spine (posterior pelvic tilt) to compensate for the lack of ankle mobility. Knee pain, ankle pain, and shin splints can result from restricted muscles of the lower leg.

Fixing Tight Ankles in Rowers

In a seated position with one leg outstretched, begin by foam rolling the calf muscles one leg at a time, covering both the middle portion (gastrocnemius) of the calves as well as the outer portion (soleus). Go slowly and methodically. If this is too easy, place one leg on top of the other to add pressure to the bottom leg receiving the manual therapy. Once you have made several broad strokes over the calves, use a tennis/lacrosse ball to go through again and search for trigger points.

Work from the base of the ankle all the way to the top of the lower leg, sitting on each painful point for at least 30 seconds. You may then do the same on the tibialis anterior, the large muscle running along the shinbone. Use only the tennis/lacrosse ball, not the foam roller, and be careful not to roll along the shinbone. Sitting in a chair or on a bench, place the ball under one foot (no shoes, bare feet or socks for this part) to roll the plantar fascia. Apply pressure as necessary, just roll over the area. This is great to do while on the computer, watching TV, etc. Once repeated for both sides, move to dynamic stretching for the ankles as shown in the video. Make sure to keep your weight on the heel throughout the movement. After dynamic stretching, try to sit in the deep squat for 1-3 minutes. This will be difficult for many on the first attempt, but this is great to do for full ankle range of motion.

Video: Ankle Mobility for Rowers – https://youtu.be/TElkXPnsTJ4

Ankle Strengthening for Rowing

The ankle muscles of the calves and shins tend to need more loosening than strengthening, thanks to a stroke cycle that relies heavily on these muscles. I do not believe that additional ankle muscle strength training is necessary for rowing, as compound strength training (squats, deadlifts, etc.) as well as rowing and common forms of cross-training all serve to develop these muscles. However, one effective way to combine training is to perform the self-massage work to increase range-of-motion (ROM), then stretch the area via the deep squat or the dynamic stretching, then do some local strength training for the area such as full ROM calf raises. Stand on a raised area like a step so you can descend as far as your flexibility will allow, pause for 1-3 seconds there, then flex the calves to raise as high as possible, pause for 1-3 seconds there, and do 1-2 sets of 10-15 reps in that same style. This combination of massage, stretch, and full ROM movement can be great for improving movement quality.

In order to enact significant, lasting change, a dedicated comprehensive program that involves all modalities is critical. I recommend focusing on one problem area at a time, at least one 10-15 minute session per day. Spending 20 minutes a day working on mobility for 2-3 weeks while watching a TV show, for instance, is a great way to progress toward full function. Foam roll, perform self-manual release on specific trigger points, and stretch, then make sure to perform additional strengthening exercises while implementing proper form into your rowing and erging training. Once full function is achieved, daily maintenance is simply performing daily activities from that now-strong position that your body can now adopt as normal positions.

This Post Has 2 Comments

I have been searching for an interview I once read – where the coach (?) of the men’s GB 8+ was discussing the difference in training leading up to their gold in Sydney Olympics 2000. He specifically mentioned the on land training which focused on weights and RP3 work as being key to bringing out the best heart rate work in each individual athlete. I would love to have the article. Can you assist me?

Dear Ann,

we have checked within our team. We do not recall this interview. Maybe someone of our audience does…

Volker